Tag Archives: Reform Judaism

“Today, half of all married Reform Jews have non-Jewish spouses, and 80 percent of those who married between 2000 and 2013 wed non-Jewish spouses”

Considering the failure of acknowledging Patrilineal Descent for the Reform Movement

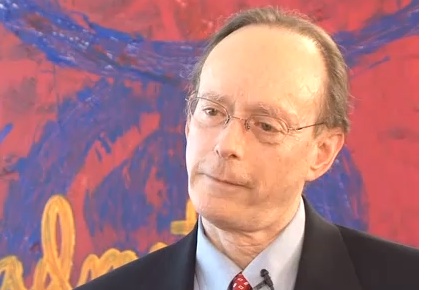

In 1983, the Reform Movement made the decision to grant any child born of a Jewish father automatic membership in the Jewish People, a policy otherwise known as patrilineal descent. Indeed, the decision of the Central Conference of American Rabbis was truly radical: it “transformed the halachic formulation of ‘the child of a Jewish mother’ to the ‘chile of a Jewish parent’” in delineating the transmission of Jewishness from one generation to the next; moreover, it stipulated that no child, whether born of a Jewish father or mother, was officially Jewish until he/she complete a bar/bat mitzvah or engaged in public acts or ceremonies of Jewishness. The impact was immediate: conversions to Judaism dropped by 75%. Following the patrilineal descent decision, only 5% of non-Jewish fiancé(e)s in prospective intermarriages converted to Judaism. The ancient Jewish club now had some members who did not recognize other club member, creating confusion. Worse still, the overwhelming majority of those granted this new club membership threw away their membership cards. As a result, membership in the Jewish club has been profoundly devalued.

Though the Reform Movement instituted patrilineal descent as a means to combat the problem of poor Jewish identity among children of intermarriage, the result has been the exact opposite. Among the 30% of mixed marriages who are raised as Jews, the vast majority had Jewish mothers. Even when the Jewish parent desires to raise the children as Jews, this is only likely to happen when the Jewish parent is a woman. This may seem surprising since the child of a Jewish father most often carries the father’s name and is frequently assumed to be Jewish by acquaintances. Nevertheless, the factual evidence is clear: whether by virtue of genes, tradition or culture, Jewish mothers are much more effective at transmitting Judaism to their children than Jewish fathers even if they so desire.

Scott A. Shay, Getting Our Groove Back: How to Energize American Jewry, 2nd ed. (Jerusalem & New York: Devora Publishing, 2008), 155.

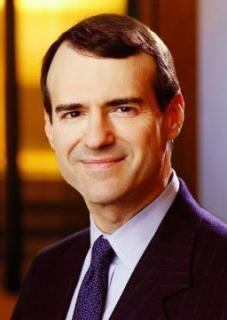

Gary Rosenblatt Considers Rabbi Rick Jacobs Statements about Intermarriage

Consider this excerpt from the major address given by Rabbi Rick Jacobs, president of the Union for Reform Judaism, at last month’s biennial of the Reform movement in San Diego.

“Incredibly enough … I still hear Jewish leaders talk about intermarriage as if it were a disease,” he told some 5,000 constituents. “It is not. It is a result of the open society that no one here wants to close. The sociology is clear enough; anti-Semitism is down; Jews feel welcome; we mix easily with others; Jewish North Americans (researchers say) are more admired overall than any other religious group. So of course you get high intermarriage rates — the norm, incidentally, in the third or fourth generation of other ethnic groups as well.

“In North America today, being ‘against’ intermarriage is like being ‘against’ gravity; you can say it all you want, but it’s a fact of life. And what would you prefer? More anti-Semitism? That people did not feel as comfortable with us?

“In any event, we practice outreach because it is good for the Jewish people. Interfaith couples can raise phenomenally committed Jewish families, especially when they do it in the Jewish community that is offered uniquely by the Reform movement.”

It’s true, as Rabbi Jacobs suggests, that interfaith couples can raise deeply committed Jews. I admire him and his work, and I hope his movement is successful in its ambitious plans to make that happen. But the jury is definitely out, with demographic experts debating whether the glass is half full or half empty, based on the findings of the recent Pew Research Center study on Jewish identity. The optimists acknowledge that while it is far more likely that children of intermarriage say they have no religion, 59 percent of that cohort who are adults under 30 say they are Jewish, a significant increase in recent years. “In this sense, intermarriage may be transmitting Jewish identity to a growing number of Americans,” write Pew researchers Greg Smith and Alan Cooperman.

Others say that only a small percentage of adult children of intermarriage marry Jews, and that based on projections of current data, less than 10 percent of them will in turn raise their children as Jews. Sociologist Steven M. Cohen cites the remark of the late American Jewish Committee sociologist Milton Himmelfarb when asked what to call the grandchildren of intermarried Jews. “Christian,” he said. (Cohen adds: “He was approximately 92 percent correct.)

Commenting on Rabbi Jacobs’ biennial remarks, Cohen said he thought it “irresponsible” for the Reform leader not to promote Jews marrying Jews. “Isn’t it an inherent obligation” for him to do so? he asked. And just because it may be going against the popular grain, “does that mean rabbis shouldn’t encourage Shabbat observance, keeping kosher, etc.?”

Gary Rosenblatt, “‘Being Against Intermarriage is Like Being Against Gravity'”, The Jewish Week (17 January 2014), 7.

“Not much changed from earlier decades in the Reform synagogue during the 1950s and well into the 1960s”

To a great extent, not much changed from earlier decades in the Reform synagogue during the 1950s and well into the 1960s, though, by the late 1960s, as we will see, the synagogue had become a very different place from what it was in the 1940s and 1950s. Rabbi Joseph Narot came to Miami’s Temple Israel in 1950, eliminated head covering and prayer shawls, and frowned upon the bar mitzvah ceremony. At Pittsburgh’s Rodef Shalom, Rabbi Solomon B. Freehof put the normative position of the early postwar period well: “We believe that the essential of the worship of God is the ethical mandate and that the ceremonial is incidental, if anything. That is our principle…. We shall never make a religion for us out of all these observances. . . . No rabbi will ever try to persuade you that God commanded you to light lights on Friday night.” The Sabbath-morning service at Temple Beth-El in Providence began at 11 A.M., ended at noon, and included a bar mitzvah! While not every Reform synagogue, by any means, fit the description of “classical” Reform—there are examples of retrieval of tradition and of restoring customs and observances absent from Reform services for decades (e.g., the sanctification of the wine, the wearing of the head covering and the prayer shawl, the use of a wedding canopy, and the construction of a sukkah)—the patterns of synagogue worship, religious school, adult education, youth groups, social activity, and social action had much in common around the country….

Marc Lee Raphael, The Synagogue in America: A Short History (New York & London: New York University Press, 2011), 132-133.

“The relativizing of the absolute is absolute in the Reform movement…”

The “sacred core” of the Reform Movement is personal sovereignty. In defining Judaism as a set of options from which Reform Jews are free to draw selectively, its adherents are ruled by what Rabbi Heschel called the “tyranny of the ego.” The center of religion becomes not G-d, but man. As we gyrate around ourselves, we cry, Vox populi vox dei.

The relativizing of the absolute is absolute in the Reform movement. Many Reform Jews think that G-d endorses what they do so long as it is “nice.” The response to intermarriage is, “It is not of great importance who they marry as long as the kids are happy.” The zone of self-regard has expanded so far as to crowd out G-d.

Rabbi Mark S. Miller, “Reform Judaism and Audacious Superficiality“, Times of Israel (7 February 2014)

“By reconsidering the policy of patrilineal descent and enforcing the Reform Movement’s stated opposition to intermarriage, the Reform Movement will clarify boundaries for itself and heal the rifts between itself and all of klal Yisrael”

At the Reform Movement’s November 2005 biennial convention, the president of the Movement, Rabbi Eric Yoffe, said that “by making non-Jews feel comfortable and accepted in our congregations, we have sent the message that we do not care if they convert. But that is not our message.” He continued by saying that “the time has come to reverse direction by returning to public conversions and doing all the other things that encourage conversion in our synagogues.” The same reasoning could be used with respect to patrilineal descent. By telling Jewish fathers that their children are Jewish, the Reform Movement gives the impression that it sanctions intermarriage by continuing to tolerate clergy who officiate at intermarriages. By reconsidering the policy of patrilineal descent and enforcing the Reform Movement’s stated opposition to intermarriage, the Reform Movement will clarify boundaries for itself and heal the rifts between itself and all of klal Yisrael.

Scott A. Shay, Getting Our Groove Back: How to Energize American Jewry, 2nd ed. (Jerusalem & New York: Devora Publishing, 2008),

“Little Zionist activity graced Reform congregations of the 1920s and 1930s, as classical Reform was generally anti-Zionist or non-Zionist…”

Little Zionist activity graced Reform congregations of the 1920s and 1930s, as classical Reform was generally anti-Zionist or non-Zionist, opposed vigorously to the idea of a Jewish state in Palestine or indifferent (“neutral,” many rabbis called this position, insisting that Reform Jews should not speak or teach about Zionism or anti-Zionism) to this fundamental idea. For them, as Rabbi Lazaron put it, “America is our home, and we do not [support] a philosophy or program which will jeopardize our position here.” Anti-Zionist rabbis (of varying degrees) were everywhere, including Samuel Goldenson and Jonah Wise in New York City, Lazaron and William Rosenau in Baltimore, Louis Wolsey and William Fineshriber in Philadelphia, Abram Simon and Norman Gerstenfeld in Washington, D.C., Calisch in Richmond, Leo Franklin in Detroit, Sidney Lefkowitz in Dallas, Harry Ettelson in Memphis, Louis Mann in Chicago, Solomon Foster in Newark, Ephraim Frisch in San Antonio, Morris New-field in Birmingham, Samuel Koch in Seattle, and the president of the Reform seminary, Julian Morgenstern. None went as far as Houston’s Beth Israel in 1943-1944, where a full-scale attack on Zionism was launched (“Basic Principles,” adopted in November 1943) and congregants agreed that a loyalty oath to America was required for membership. Beth Israel was but a bump in the road toward an acceptance of Palestine and Israel; what Zionist Reform rabbis of this period called the great folk movement of the Palestinian Jews was slowly entering the fabric of some of the congregations. Conservative synagogues virtually everywhere identified strongly with Zion, whereas Reform synagogues looked askance at this enthusiasm. This made it much harder, until Reform temple leaders changed their attitudes in the 1940s, for Reform congregations to attract the children and grandchildren of those east European immigrants who were moving away from orthodoxy In 1930, only half the members of Reform synagogues had family origins in eastern Europe.

A significant minority of Reform rabbis vigorously supported Zionism throughout this period, not just the rabbis with national Zionist credentials, such as Barnett Buckner, Max Heller, Abba Hillel Silver, and Stephen S. Wise, but the rank and file everywhere. Support for the Balfour Declaration and the Mandate given to Britain by the League of Nations, horror at the civil strife in Palestine, Palestine as a hope for German Jewry, and the World Zionist Organization biennial congresses and the British commissions in Palestine and American Zionist activity during World War II were regular sermon topics across the land in many Reform congregations. And another sizeable group of rabbis, while not activists in their commitment to Zionism, introduced a wide variety of programs about Palestine into the synagogue. These included art, dance, drama, literature, music, and philanthropy, and, though an emphasis on the Hebrew language in worship might have been missing, activities of all sorts revolving around Palestine filled the synagogue bulletins.

Marc Lee Raphael, The Synagogue in America: A Short History (New York & London: New York University Press, 2011), 107-109.