Tag Archives: Jews

“To feed the hunger for knowledge that exists among American Jews, we need education that doesn’t talk down to people or make them feel like children”

“You can’t bring anything Jewish to a conversation if you don’t know it” – Lawton

“If we’re just like everybody else, what are we for?” -Clive Lawton

Jews “can relax; we don’t have to worry about [quantitative] numbers”

“Jewish education in this country has given too little attention to the texts, history, and culture of the Jewish people”

This gallery contains 0 photos.

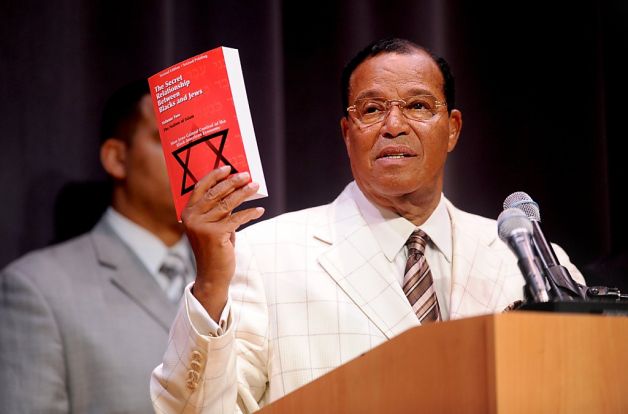

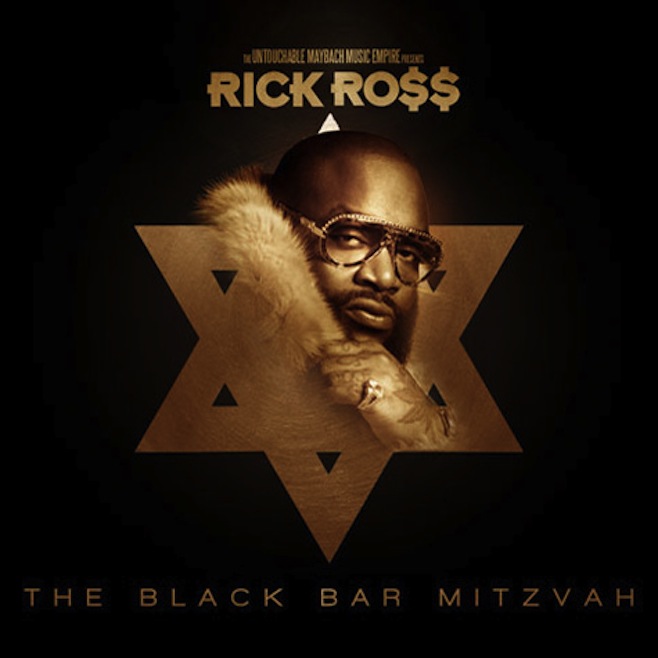

Jewish education in this country has given too little attention to the texts, history,...“Hip-hop is having a Semitophilic moment”

“If “remembering the Holocaust” is an essential part of what it means to be Jewish, then it follows that a substantial core of Jewish identity is primarily defined by heinous acts committed by Nazis upon Jews”

If “remembering the Holocaust” is an essential part of what it means to be Jewish, then it follows that a substantial core of Jewish identity is primarily defined by heinous acts committed by Nazis upon Jews. In a tragic twist of history, it is the enemy who now writes the story of Jewish identity and who determines its emphases.

Perhaps even more regrettably, this “essential” feature of being Jewish is characterized by gaping loss, appalling destruction, and unremitting sadness. Hence, according to the popular view, the most pivotal component of Jewishness actually emerged post-1933 in the form of a horrendous cataclysm that was fashioned by others; and Jewishness is devoted to recalling this nightmare so that nobody should forget what happened.

…

Let there be no doubt: it is vitally important to remember the Holocaust and its lessons. But it is also vitally important to acknowledge that remembering the Holocaust is no more essential to being Jewish than remembering 9-11 is essential to being American. Both memories are of great consequence, but neither shapes the “essential meaning” of the nation.

Rabbi Dr. Daniel Schiff, “Remembering Our Identity”, eJewish Philanthropy (2 January 2014).

“Jews don’t give to organizations but to causes…”

Jews don’t give to organizations but to causes. Organizations need to see themselves as tools for donors and users rather than vice versa.

This is not merely semantics. It implies seeing the relation between missions and users, donors or members in a completely different light. Organizations need “network weavers” rather than fundraisers, facilitators rather than directors, and catalysts instead of organizers.

Andres Spokoiny, “Study Points The Way Toward More Avenues to Jewish Life”, The Jewish Week (8 November 2013), 43.

A difference between Jews who do and do not feel it is a liability to be a Jew

His interest in youth was closely allied to education. He cherished a great respect for learning….

He said, “There are those among our people who feel it is a liability to be a Jew. This does not occur to the Jew who has had an adequate background. The glories of his people, the luster of their history, the magnificent values which constitute the essence of his religion, the recognized fountainhead of all religions of modern civilizations, condition him to avert such self-hatred and self-pity. He can understand why the martyrs in Israel’s history died for their ideals. Their pride of ancestry gave them courage to accept and endure the most extraordinary punishment. Their thorough appreciation of their history was a sustaining force against shock and against confusion. It constituted a basis for the rebuilding of dignity and self-respect.”

Maurice Bisgyer, “Henry Monsky: His Work”, in Mrs. Henry Monsky and Maurice Bisgyer, Henry Monsky: The Man and His Work (New York: Crown Publishers, 1947), 76-77.